Sometimes, the best interviews just fall into your lap. I’ve never had any interest in boxing; if anything, a mild distaste. But when I got asked to talk to Mike Tyson for a French fashion magazine front cover in 2013, it was too exciting an opportunity to turn down.

Tyson used to be known as ‘the Baddest Man on the Planet’. In the late Eighties, he was the most famous man in the world. His brutal, medieval monsterings of hapless opponents were destructive acts of performance art. Boxing’s feral assassin, he reigned in blood.

Given his ferocious reputation, both in and out of the ring, I expected to encounter a brooding, testosterone-soaked, macho thug. Instead, I met a profoundly insecure, hesitant soul, willing to delve deep into his past and his psyche despite being patently unsure what he would find there.

The loosest of cannons, Tyson didn’t show up the next day for the French fashion magazine’s cover shoot, so they binned the feature and, instead, my interview ran in the Daily Telegraph. Here is the director’s cut.

‘I’ve had self-loathing my entire life…’

When you have been the most famous sportsman on the planet, where do you go from there? Perhaps that is the problem. The only way is down.

Only Mike Tyson wasn’t just the most famous sportsman. He was also the Baddest Man On The Planet. That was how they billed him in the late Eighties and it was impossible to argue. Iron Mike Tyson was the modern Raging Bull; an apocalyptic tornado of testosterone, self-disgust and savagery; an avenging angel force-of-nature who shredded hapless opponents like so many paper dolls.

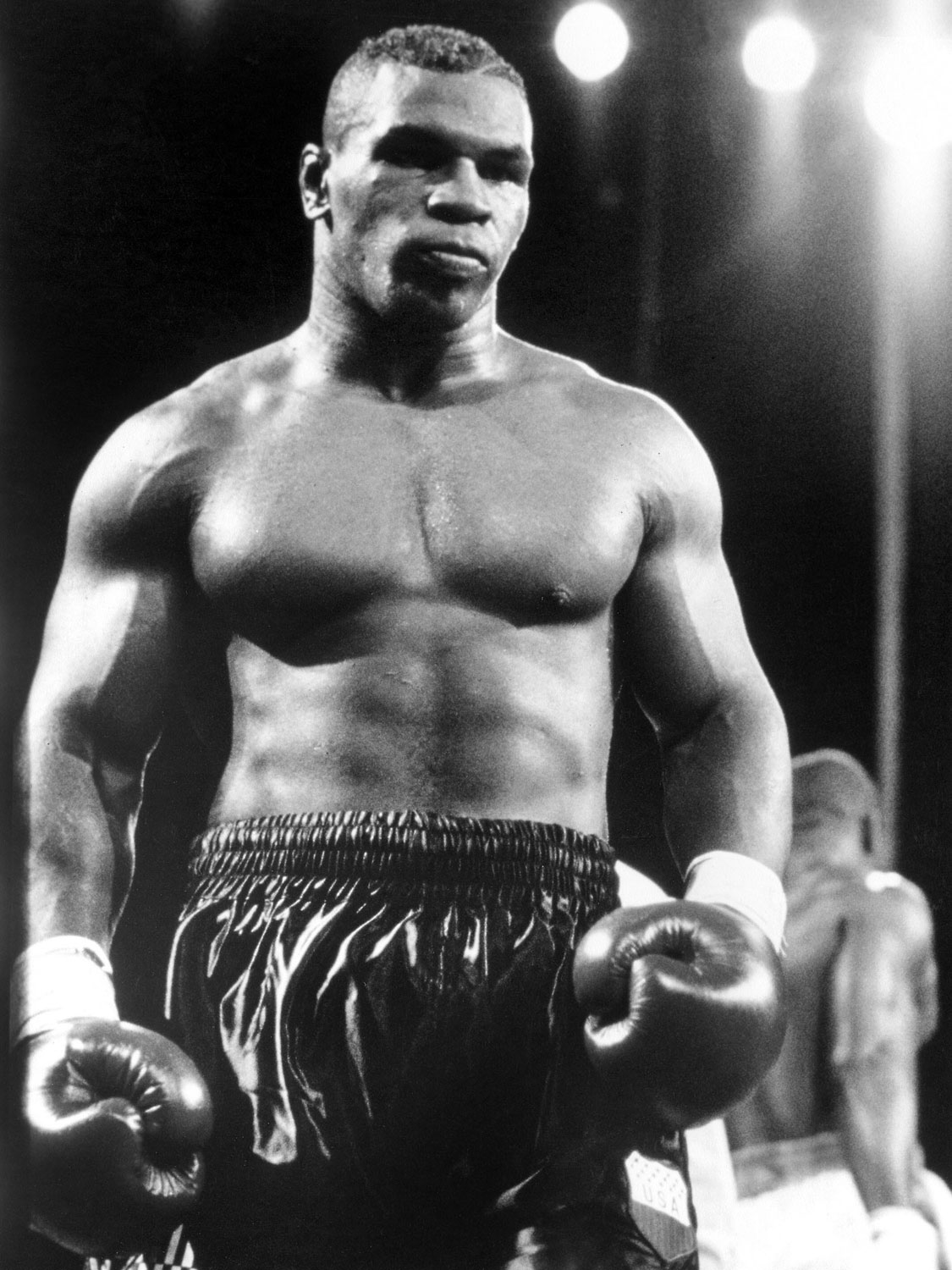

Tyson’s achievements in the ring were legion, and peerless. Boxing’s feral assassin, he was the undisputed heavyweight champion of the world at just 20. He mashed up giants of men and prize athletes such as Larry Holmes, Michael Spinks and Donovan Ruddock and made them look like children. Wild-eyed and audacious, he was a tsunami of muscle, wrath and bile – and his adrenaline-frenzied assaults always looked personal.

‘What did I want to do when I got in the ring?’ he wonders now, thinking back on his raw nights of brutality. ‘I wanted to destroy the other guy. I wanted to kill them.’

Yet the higher the ascent into the celebrity stratosphere, the greater the fall. Mike Tyson crashed and burned with the dread, unstoppable momentum of one of his own raw monsterings. He lost his world titles when the sociopathic training routines gave way to partying. There was a six-year prison sentence for rape, of which he served three. When he fought Evander Holyfield to attempt to regain his world crown, a bout seemingly watched by the entire planet and for which Tyson was paid a fee of $30m, he chewed a lump from Holyfield’s right ear and spat it onto the canvas.

After that? After that, he really started going downhill. There was another jail term, for a street fight. His chaotic personal life and financial affairs led to bankruptcy. Retired from boxing and reduced to sparring for cash in the foyer of Las Vegas casinos, he admitted to drug addiction after yet another arrest. ‘What did I turn into?’ he later reflected. ‘I was a fucking fat cokehead!’

The shaming of The Baddest Man On The Planet was complete.

Except that, somehow, shocked from his narcotic and alcoholic stupor by the death of his four-year-old daughter, Exodus, in a tragic domestic accident in 2009, Tyson began to fight back. He has attempted to eschew drink and drugs, proudly telling Ellen DeGeneres in 2011 that he was ‘two years sober’. Recently, he toured 36 US cities with Undisputed Truth, the Spike Lee-produced one-man-show confessional that features him reciting a monologue penned by his current, third wife, Kiki Spicer.

A tell-all, hopefully cathartic autobiography of the same title is due this winter. In 2013, against all the odds, Mike Tyson has conquered his myriad demons and rejoined the human race.

Or has he?

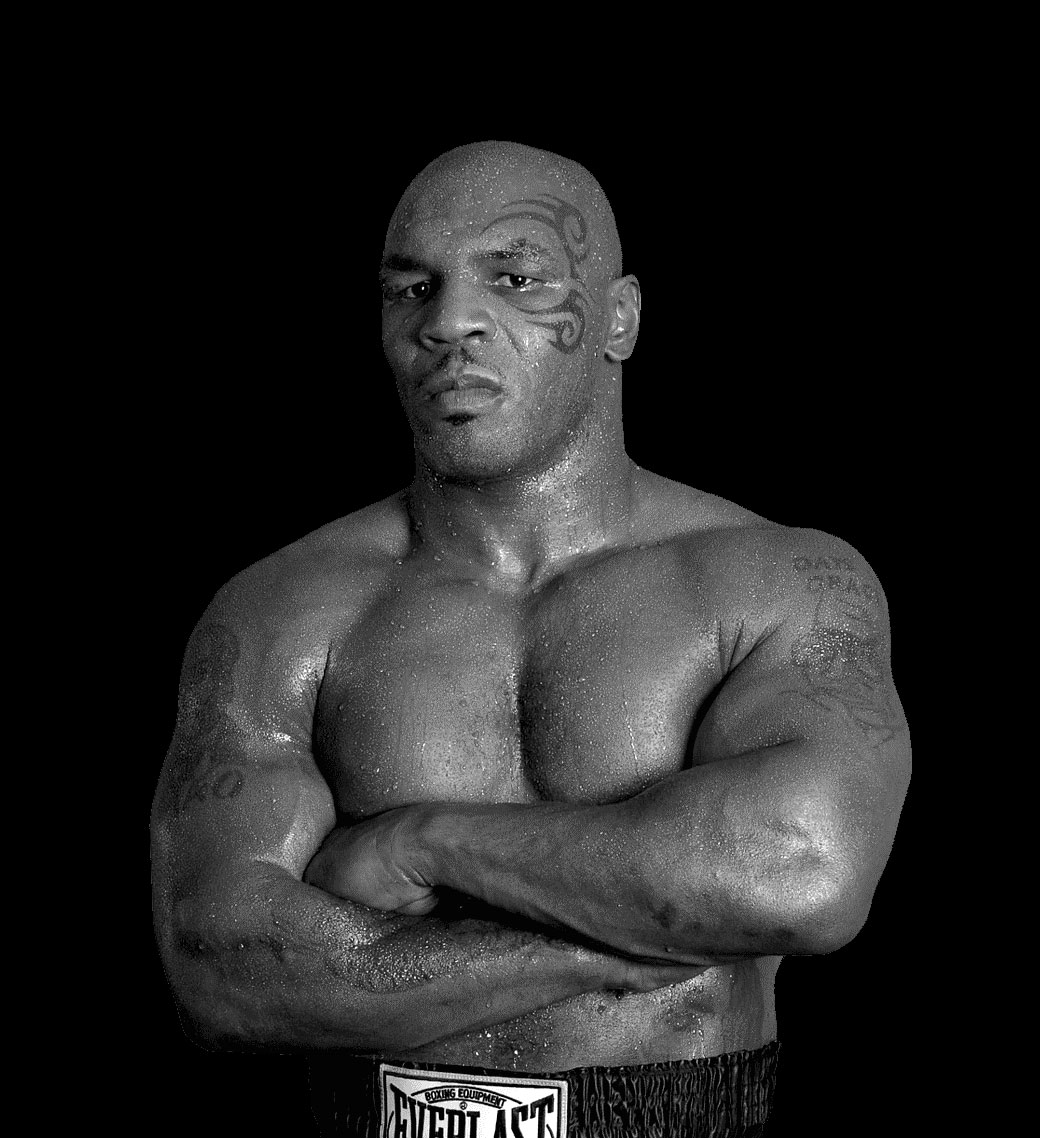

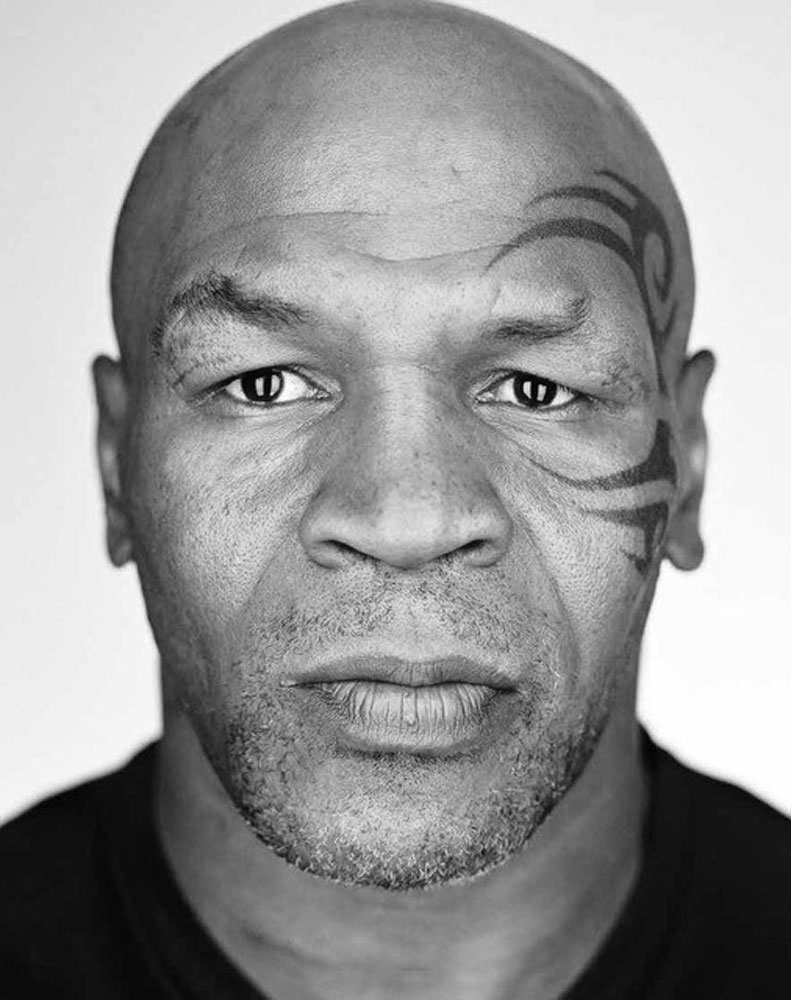

Coiled into a hotel-suite chair on a late summer’s New York afternoon, Mike Tyson still exudes charisma and menace. His preternaturally toned physique may be long gone, and he looks every one of his 47 years, but his unmistakable visage retains its innate capacity to intimidate. For the duration of our interview, he flicks grapes high into the air and catches them in his mouth; when he turns to the window, the sunlight glints on the tribal tattoo that sprawls across half of his face.

His voice comes as a shock, as it does every time you hear it. Far from the resonant baritone that his presence and stature lead you to expect, Tyson instead answers my questions in a high-pitched gabble, rendered sibilant by a slight lisp. Words tumble over each other: frustrated, he frequently abandons a response after a few seconds and begins it again, to try to get a better handle on a question.

Tyson has flown into New York from his Vegas home to launch another of his post-fight careers, this time as a boxing promoter. The next night, Iron Mike Promotions are staging a US super-featherweight title bout at an upstate casino venue. I ask him what he learned about promoting from his career-long dealings with Don King, a man with whom he was frequently involved in legal action.

‘Hey, I never learned nothing about how to sell a fight from that man!’ he grumbles. ‘My deals will be different. It’s gonna be the fighters that get paid. I don’t wanna give no damn manager no money. I don’t want to hear that crap.’

This mix of positivity and petulance sets the tone for what will be a frank, fraught and frequently confusing interview. With his burgeoning media career and various entrepreneurial sidelines, the purportedly newly sober Mike Tyson should be talking the language of recovery and redemption. He pays lip service to it, but he never sounds convincing – or convinced.

Typical is our exchange when I suggest to him that he must have found some inner peace to be able to undertake his current multiple exercises in introspection: the autobiography, the stage show, a fly-on-the-wall Being: Mike Tyson TV series. Would he have been able to do this stuff a few years ago?

‘Hey, I feel comfortable with being who I am when it comes to talking about myself,’ he begins. ‘It is pretty interesting. I find out a lot about myself when I start searching in my past. It can be very scary.’

The past is another country, and sometimes we don’t live there because it drove us out.

‘Holy Moses!’ he concurs. ‘Retrospect is the word. Reflection is shameful sometimes, but healing. I was an animal for years but now I deal with life differently. I want to be humble, to the best of my ability…’

He pauses. There is a visible struggle between the therapy speak he has absorbed over countless years of sessions, and the street fighter who is never far beneath his surface.

The street fighter wins.

‘I’m not humble,’ he confesses. ‘I haven’t got a humble bone in my body. But I portray myself as being humble, and I hope that it becomes real.’

Mike Tyson is the strangest mix of a hugely conflicted human being… and an open book. He runs through the film reel of his life’s events, often with an air of horror, like a man who cannot quite believe everything that has happened, and is still searching for answers. Despite the looming sense of shame that he has clearly never escaped, he is touchingly willing to talk about his desperately dysfunctional childhood.

His father, a street hustler, quit the family home just after Tyson was born, leaving his mother to raise three siblings in Brooklyn alone. It was not a task she was well equipped to accomplish.

‘I don’t know how to explain my mother,’ admits Tyson. ‘I don’t want to say she was a prostitute, because she wasn’t on the street, but she slept with men for money. She had been to college and everything but she didn’t have good skills. I loved her yet she made me feel bad all the time. She was a full-blown alcoholic. Drinking, smoking, men, and sleeping for hours… Goddamn!

‘We were always poorer than anybody and it made me feel like my family was less worthy than anybody else’s. So when I was a young kid I used to get picked on and bullied and I would go robbing, hoping guys would accept me in their gangs and stuff. All the time, I used to dream about kicking everybody’s fucking ass and killing some people.’

A frequent resident of Brooklyn and Bronx police cells by the age of 13, the adolescent Tyson had no interest in the Seventies boxing goliaths of Ali, Foreman and Frazier. He only ever saw one Ali fight, on a TV in a bar: ‘I was doing my pickpocketing shit and it was easy, because everybody was watching the fight.’

Despite this indifference, Tyson excelled at boxing in reform school, where an ex-pugilist teacher spotted him and delivered him to the tutelage of Cus D’Amato, a septuagenarian trainer who had nurtured Rocky Graziano and Floyd Patterson. Tyson arrived in his care a ticking time bomb of volcanic hormones, wrath and insatiable self-disgust.

Did you realize immediately that you were brilliant at boxing?

‘I never realized I was brilliant! I never thought I was nothing! I was just a thief; there was nothing good about me. I was a little scared boy who wanted to be a tough guy. I thought I was shit, until Cus told me I was a gigantic reptilian Tyrannosaurus Rex monster. He built up my confidence, but he built it so high that he made me into a fucking megalomaniac.’

D’Amato also turned the permanently enraged Tyson into a fearless, ferocious fighting machine. His speciality? Psychotic ultra-violence. After turning professional at 18, he won his first 19 fights by knockouts. Twelve of them came in the first round: most of them in the first minute.

How did you get so psyched up to charge out of your corner in those first few seconds and wreak utter, bloody carnage?

‘Cus used to have me professionally hypnotized two or three times a day – before sparring, before training and before fights. My objective was to destroy.’

Did you ever feel sorry for the guy you were beating to a pulp?

‘No, because Cus didn’t like me being sensitive like that. He wanted me to be emotionless. He said feelings mean nothing. Feelings have nothing to do with your life. The only thing that they do is distract you.’

This is the Tyson we remember, of popular memory and legend; the barbaric automaton, the genius brute, red of tooth and claw and powered by homicidal fury. Hell-bent on annihilation, he virtually dismembered all that came against him, rising through the ranks until he defeated Tony Tucker in 1987 and became the first fighter to hold all three world heavyweight championship belts.

Thus began his imperial period during which he routinely – and with maximum violence – swatted away challengers like flies. His apex arguably came in June 1988, when he faced Michael Spinks in a title bout billed as the evenly balanced battle of the two finest fighters on the planet. Tyson had Spinks on the canvas and out for the count with 30 punches in 90 seconds.

He must have felt on top of the world.

‘Shit, all those fights are like a blur to me now…’ the man in the New York hotel room tells me, before allowing a truer memory to surface. A smile spreads across his face: ‘Man, I felt invincible. I felt like a god.’

Yet Mike Tyson was a god with feet of the finest, weakest clay. Naturally, his precipitous rise to success had not eradicated his urge towards self-destruction: it had merely given it a bigger stage to act out upon. After the death of D’Amato, he sacked his long-term coach, Kevin Rooney, as rumors spread that he was training less and partying harder. In February 1990 in Tokyo, in one of the biggest upsets in sports history, Tyson lost his world crowns to 40-1 rank outsider Buster Douglas. It was the first time he had been knocked out.

His personal life had similarly dissolved into anarchy. There had been a tempestuous, allegedly violent marriage to soap actress Robin Givens, who divorced him after telling US chat show host Barbara Walters that life with Tyson had been ‘torture, pure hell, worse than anything I could possibly imagine’.

So what? Mike Tyson was still the Baddest Man On The Planet: he was unlikely to go short of female company. Boxing groupies queued up for him.

‘There was just so many women, and I never treated them with respect because I had seen men have no respect for my mother,’ he says now, with a mirthless laugh. ‘It got to like I just wanted to hold someone, so I’d make sure someone was next me every night just in case I wanted to do it.’ Another laugh. ‘Like most celebrities, I didn’t want a wife – I wanted a slave. A hostage.’

It was this brutish, unreconstructed attitude that led to Tyson standing trial in Indianapolis in 1992 accused of the early-hours-of-the-morning rape of 18-year-old beauty queen Desiree Washington (a crime of which he still vociferously and bitterly pleads innocence in his Undisputed Truth tour). His truculent, hostile attitude in court led to an inevitable guilty verdict. He spent the next three years in prison.

Notably, Tyson still talks about his incarceration with an air of simmering resentment.

‘I went in 270lbs and I came out 216lbs,’ he remembers. ‘And I always knew I’d box again and I’d be world champion again. When people like Bowe and Holyfield, or Lennox and McCall, were fighting for the titles, I’d phone my friend’s house and listen to the fights down the phone.’

Did you come out of prison a better man, or just an angrier one?

‘I came out real angry and bitter. That’s why I got in more trouble and I didn’t care who I hurt. I was a real bad, bitter person.’

Whipped back into shape by his time in prison, Tyson regained two of his three heavyweight world title belts within 18 months of his release. What followed was grisly beyond belief, and the episode that will forever define him in popular culture, as he left Evander Holyfield’s ear in tatters in the Vegas MGM Grand Garden Arena ring.

What was he thinking of when he bit him? Did he hate him? I have hardly got the question out before Tyson interrupts me.

‘I hated everybody!’ he spits. ‘I hated myself! That was what it was all about – controlled hate!’

What was it like to become the world’s pariah at that moment, a global object of scorn and ridicule? As he struggles to formulate an answer, an agitated Tyson falls into the universal sportsman’s habit of discussing past events in the present tense.

‘This savage killer they are all afraid of… I’m not that guy,’ he says, the words fired out like bullets. ‘I wish I could be that guy but I’m not. I’m a scared, insecure little kid. Can you imagine? The world thinks I’m a savage and I’m an afraid little boy!’

Banned from boxing for a year, Tyson had another of his serial brushes with notoriety on his return. Before his doomed, final attempt to win back a world title, against Lennox Lewis in 2002, he taunted the British fighter with some spectacularly misjudged pre-fight hype talk: ‘I want to eat his heart! I want to eat his children! Praise be to Allah!’

On some topics, Mike Tyson’s remorse can appear crocodile tears. On this one, his contrition is clearly genuine.

‘Oh fuck!’ he groans, rocking in his chair. ‘The disrespect! Can you believe that bullshit? I am so embarrassed and humiliated at what I said, and it will always linger around me because it is in writing. Nowadays I’m a pussy. I want to make amends but…’

His voice falls away. He lobs another grape into his mouth.

‘… I don’t know how to do it.’

Tyson’s nadir was yet to come. Battered, beaten and broken, he finally retired from the ring in 2005 after losing a string of no-hoper bouts: ‘It was getting ugly. I was getting my ass kicked. It hurt.’ He drifted into a life that consisted of little more than ‘hanging out, every day, getting high’. There was a conviction for cocaine possession; an arrest after a scuffle with a paparazzo at LAX.

They were dark days. There must have been a lot of self-loathing.

‘I have self-loathing now!’ he interjects, brusquely. ‘I’m trying to stop it. I’ve had self-loathing my entire life. I’m always gonna be depressed. I’m gonna be that sad guy for the rest of my life. I just have to work with it, that’s all.’

So how is Mike Tyson’s work going, this project of attempting to rebuild his life – his very self – and to put his history of abuse, barbarianism and subterranean self-esteem behind him? It has to be judged, at best, to be a work in progress, and one that is prone to debilitating, typically self-destructive failures of will.

Throughout a tortured life in which Tyson has mentally never truly left behind the mean Brooklyn streets of his childhood, he has been a regular user of both cocaine and marijuana. Yet the most seductive siren voice to him remains the demon drink.

‘I’m an alcoholic,’ he tells me, bluntly. ‘I’m an alcoholic but I never tell people I’m an alcoholic because I’m embarrassed to say I’m an alcoholic, so I say I’m a drug addict. That’s more hipper than being an alcoholic.’

In fact, having publicly professed to be sober for more than four years, Tyson has recently lapsed and started to drink again. I ask him: Is it two steps forward and one step back? He abruptly leans forward, and raises his voice: ‘It’s more like one step forward and three steps back!’ As we speak, he has been sober for less than a week.

‘But I don’t wanna go that road no more,’ he vows. ‘So now I’m doing therapy and rehab again; starting all over on the 12 steps. I’m trying to live the sober route because I know if I don’t, I will die. When I am in my addiction I am a vicious, addict thief. Now I always want to be of service, and I want to be on my knees in that service, because when I think I am a superstar big shot, that is when I get high – and then I will die.’

It’s a typically candid, confused confession, and it leaves me in the bizarre position of having the human urge to put a consoling arm around the shoulders of Iron Mike Tyson; to assure him that everything is going to be OK.

Surely, I suggest, you are gradually growing happier in your skin; getting nearer to being the person you want to be.

Tyson looks skeptical. ‘I hope so, but it’s scary,’ he says. ‘As you get older, you get scared. Can you believe that? You are scared. You’re born into this world crying and you don’t know if you are going to die disappointed. I don’t want to die disappointed.’

He pauses, collects himself, attempts to count his blessings.

‘I’m just trying to be grateful to be the person that I am, and I’m very grateful to have a wife and children that love me. Because mostly I don’t ever think I’m worthy of love, but I’m grateful to have it.’

If Mike Tyson were to die tomorrow, what would he choose as his epitaph? And the perennially troubled former Baddest Man On The Planet regards me with a stare that implies that this may just be the dumbest question he has ever heard.

‘I dunno. I might not have a gravestone. Or maybe it would just say, “I was here”.’